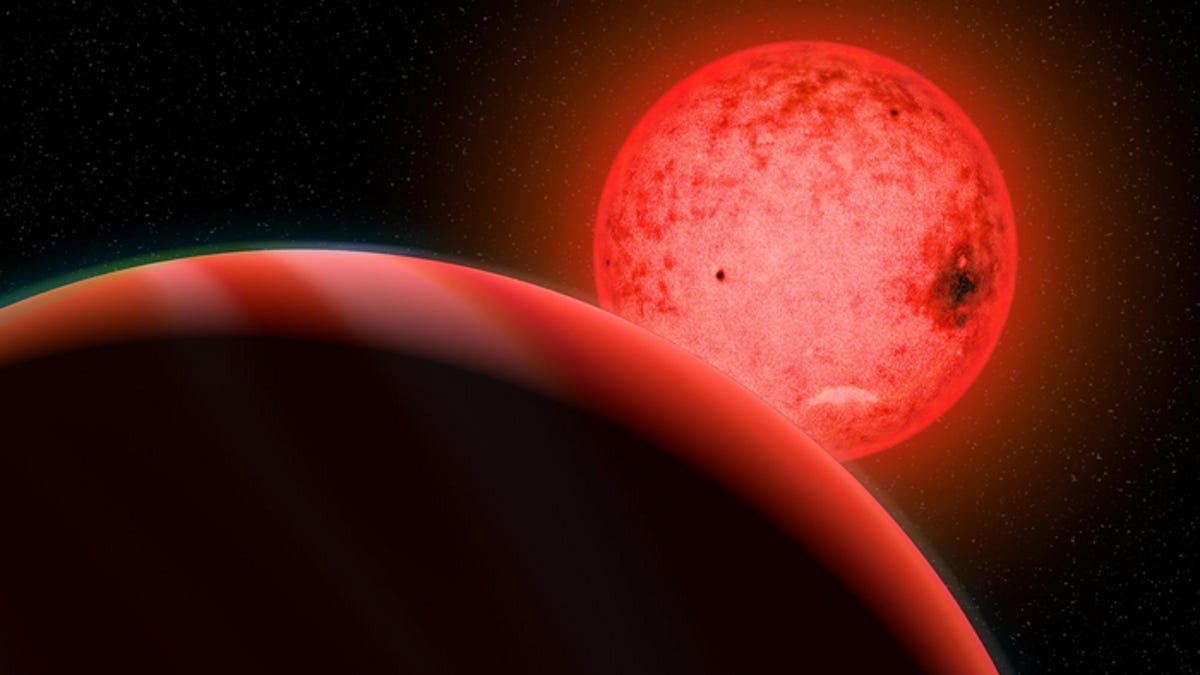

An artist’s conception of a large gas giant planet orbiting a small red dwarf star called TOI-5205.

Katherine Cain, courtesy of the Carnegie Institution for Science

About 285 light-years from our solar system lies a lovely, minimalist cosmic neighborhood. Its “sun,” you might say, is a particularly small, glowing crimson body named TOI-5205 — a red dwarf. And submerged within the void of space, we’ve now located exactly one planetary friend of TOI-5205, according to a paper published this month in The Astronomical Journal.

Scientists call it TOI-5205b. Yes, that moniker is based on formality, but you must admit it’s also kinda cute.

OK, but here’s the thing.

It’s pretty typical for red dwarfs to anchor planets (often several), because these stellar bodies are only about half as hot as the sun and have very low luminosities, yet are known to average extremely long lifespans. Even TOI-5205 is measured to be about 3,500 Kelvin (3,227 degrees Celsius), in contrast to our 5,800 Kelvin (5,526 degrees Celsius) sun.

However, there are two peculiar aspects of TOI-5205 and TOI-5205b’s companionship.

First off, red dwarfs aren’t expected to host gas giant planets — but that’s exactly what TOI-5205b is. Second, and most importantly, sunlike stars in general are usually thought to host planets significantly tinier than themselves.

“The host star, TOI-5205, is just about four times the size of Jupiter, yet it has somehow managed to form a Jupiter-sized planet, which is quite surprising!” Shubham Kanodia, an astronomer at the Carnegie Institute of Science and co-author of the study, said in a statement. “Based on our nominal current understanding of planet formation, TOI-5205b should not exist.”

“It is a “forbidden” planet.”

To put this size discrepancy into context, Kanodia offers a compelling analogy.

You can think of a Jupiter-like planet orbiting a sunlike star as a pea going around a grapefruit. TOI-5205b orbiting TOI-5205, though, is more like a pea orbiting a lemon.

To be clear, something as big as Jupiter isn’t to be discarded as diminutive — let alone something multiple times as big as Jupiter. Basically, if you took every planet in our solar system, slapped their masses together and multiplied the sum by two, you’d get a chunk about the size of our beloved giant.

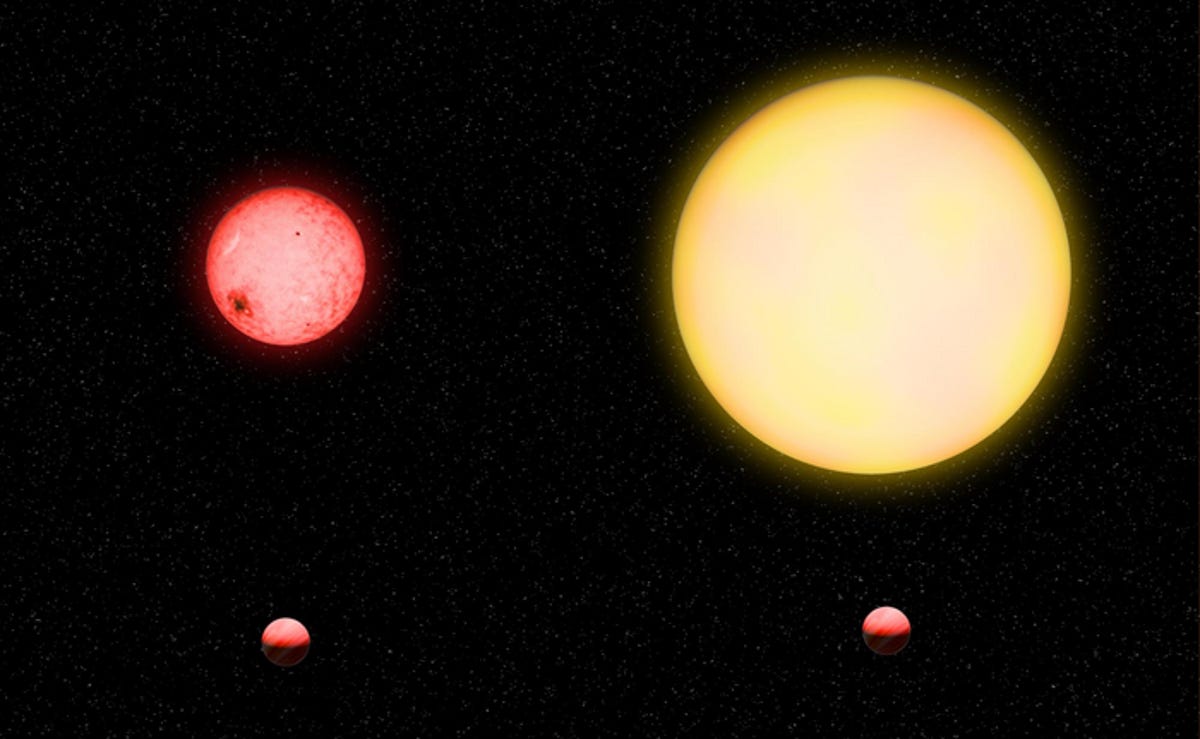

Still, hundreds of Jupiters could fit inside our sun. Only four TOI-5205b’s could fit inside its “sun.”

A size comparison showing what TOI-5205b would look like orbiting its own star (left) and the sun (right).

Katherine Cain is courtesy of the Carnegie Institution for Science.

So, what might’ve happened long ago, as the TOI-5205 star system was first founded, to create such a strange pairing of cosmic bodies? The simple answer is that we don’t know yet. Kanodia and fellow researchers have some leads but ultimately say they’ll need to observe it in greater detail to solve the mystery. And solving this mystery may rearrange our knowledge of planet formation theory.

“We know that TOI-5205 b exists, therefore there is some gap in our understanding of these disks, or planetary interiors, or the process of planet formation (or the most likely scenario, all of the above!),” Kanodia wrote in a blog post about the discovery.

In short, as young stars traverse the depths of space, they tend to have disks of interstellar gas, rocky shards and dust surrounding them.

An established model of planet formation — for gas giants like Jupiter and TOI-5205b — says you need about 10 Earth masses of the disk’s material to make a rocky planetary core. Then, a ton of gas from the disk starts bunching around that core and eventually forms into massive, exuberant worlds such as our solar system’s tangerine-striped icon.

But TOI-5205’s initial disk isn’t expected to have had enough of those gas giant building blocks to form a Jupiter-esque body.

“In the beginning, if there isn’t enough rocky material in the disk to form the initial core, then one cannot form a gas giant planet,” Kanodia said. “And at the end, if the disk evaporates away before the massive core is formed, then one cannot form a gas giant planet.”

“Yet,” Kanodia continued, “TOI-5205b formed despite these guardrails.”

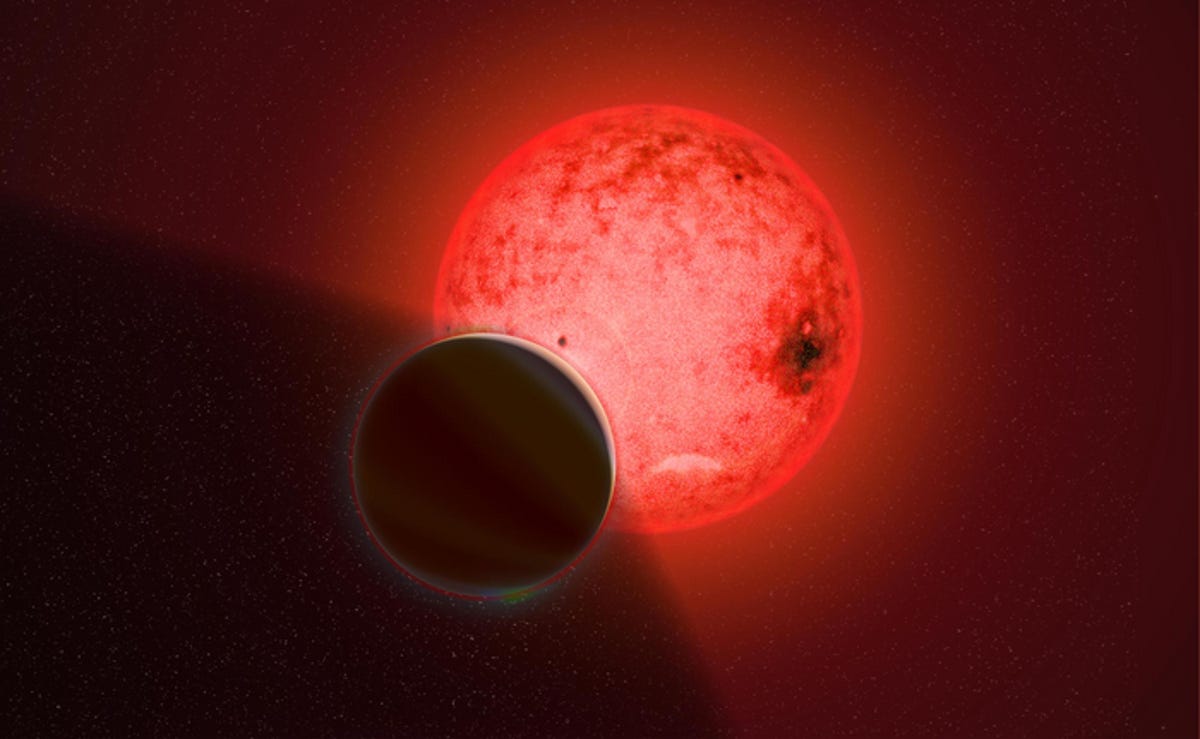

Katherine Cain, courtesy of the Carnegie Institution for Science

On the bright side, however, because the size ratio between the deep space duo is so close (when TOI-5205b passes in front of its star from our vantage point, it even blocks a whopping 7% of the orb’s light) the pair is quite easy to study.

The researchers are especially interested in using the trailblazing James Webb Space Telescope to understand the TOI-5205 star system’s unusual backstory. Built to assess the cosmos with an unfiltered lens, in just over a year the JWST has already managed to find a whole new world on its own, paint a detailed picture of a broiling hot orb‘s chemical fingerprint and could soon even scope out what might be the youngest exoplanet on record.

At the end of the day, Kanodia writes in his blog post, the question is this: “TOI-5205 b — while definitely an outlier — isn’t the only one. If so, how frequently do these forbidden planets form?”