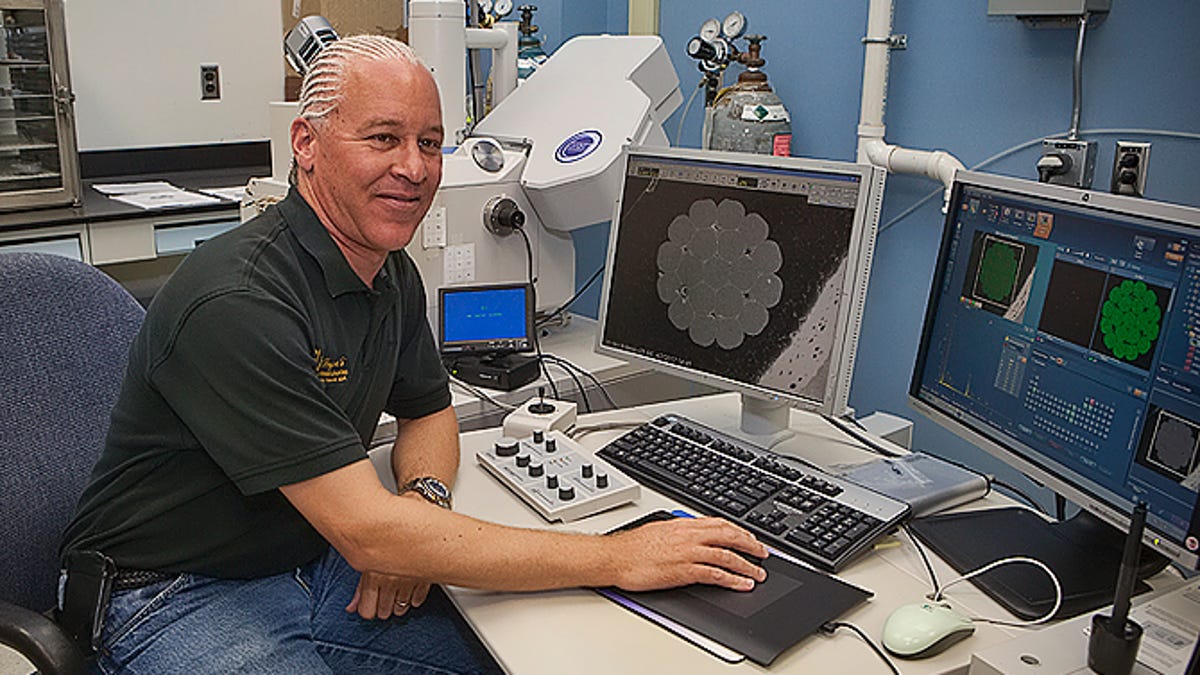

Robert Bryant at work, circa 2012.

Sean Smith/NASA

![]()

Robert Bryant was part of a team at NASA in the early 1990s tasked with coming up with a new material for use in the next generation of civilian supersonic aviation – high-speed planes that could carry 400 people and fly at Mach 2.0 so they could journey from Los Angeles to Tokyo twice a day.

And the new material needed to be built with commercially available polymers and chemicals that could basically be purchased “with a credit card,” the NASA chemist said. That’s because using readily available components to make new synthetics is one of the fastest ways to get products to market.

While Bryant succeeded in creating a high-performance polymer for constructing the plane’s main components, like the wings, his invention, called LaRC-SI (which stands for Langley Research Center Soluble Imide), wasn’t chosen for the project. And that’s where the story might have ended, just another interesting invention developed as part of a publicly funded R&D project at NASA.

But Bryant didn’t want LaRC-SI to die. So he did something few researchers do – he convinced his supervisors to let him figure out if there were other potential uses for his new material. Turns out there was one – LaRC-SI (he admits the name doesn’t roll off the tongue) could be used as a coating for the “leads,” or wires that connect pacemakers to your heart. So after figuring out how his new material could be made, Bryant worked with manufacturers who helped create the leads for Medtronic, a health care technology company that saw the technology’s potential for use in pacemakers.

Robert Bryant: As a kid, “I did a lot of repair work on toys. … I learned how things worked – that really helped me.”

National Inventors Hall of Fame

“The innovation is not just the creation of LaRC-SI itself,” Bryant, 60, said in an interview. “It’s the effort that it actually took to get it into the commercial market, where a supply chain had to be developed, applications had to be found, and it had to get into hands that were a lot smarter and more innovative in their own ecosystem than what I thought this material could be used for.”

His perseverance in finding a commercial application for LaRC-SI has helped save nearly 700,000 people – so far. It’s also earned Bryant a place in the 2023 class of inductees in the National Inventors Hall of Fame, which has honored innovative US patent holders including Thomas Edison (for the electric lamp), Nikola Tesla (the electro-magnetic motor), Douglas Englebart (the computer mouse), Hedy Lamarr (frequency-hopping communications), George Washington Carver (peanut products) and Lewis Edson Waterman (the fountain pen).

The 2023 inductees, announced today, also include inventors who’ve worked on ideas from CRISPR gene-editing projects to CAPTCHA website security tech to wheelchair technology.

How unusual is it for researchers to find unexpected uses for their original inventions? It happens – think the weak but sticky glue developed at 3M that turned out to be perfect for Post-It Notes. Or Corning’s super strong Gorilla Glass, which proved to be too strong for car windshields but ended up decades later being tapped by Apple’s Steve Jobs for use as a scratch-resistant screen for the iPhone. Most of the time, though, said Bryant, government and private industry researchers’ ideas end up on a shelf or as a footnote in research projects.

In the case of LaRC-SI, using it as the coating or insulating material for those cardiac leads resulted in thinner leads – down from about 2.5 millimeters to 1.25 millimeters, Bryant said. And because they were thinner, Medtronic found that instead of having just two leads (or one pair) attaching the pacemakers to the left ventricle of someone’s heart, they could have eight leads (four pair). What that means is if one set fails, the pacemaker can switch to another – saving patients’ lives and also reducing the need for surgery to replace pacemakers, Bryant said.

“You can imagine that all these people are not only alive, but are living better lives because of this sort of technology,” he added.

I asked Bryant if he always wanted to be an inventor. What did he want to to be when he was a kid? He laughed.

“One of the things that I was always curious about when I was a child was how people make things and how they choose the materials they use to make them,” he said.

Did he make anything interesting as a kid? “I did a lot of repair work on toys. After toys broke, I would fix them. I learned how to use glue, I learned how to wind motors. And I learned how things worked – that really helped me. So to all the children out there, get your Lego sets.”