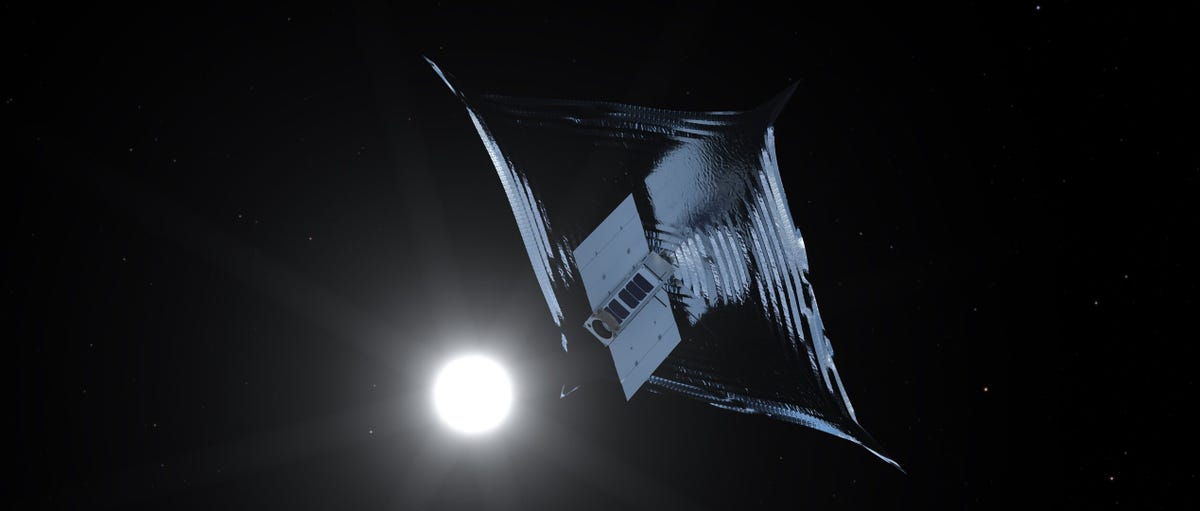

An artist’s impression of what the space sail looks like as it’s deployed from its jack-in-the-box container.

ESA

As futuristic as this sounds, real estate in space is booming. Major corporations and science research organizations are actively vying to send satellites into orbit for extraordinary reasons — developing free internet connection; enhancing GPS systems; monitoring climate change; even analyzing Albert Einstein’s trippy general relativity equations.

But while humanity continues to advance technologically, experts are growing increasingly worried about a major issue: We’ve found a new area of the universe to pollute. As of 2021, NASA said, more than 27,000 pieces of orbital debris, or “space junk,” resided in our planet’s gravitational tides — and since then, SpaceX alone has sent hundreds more satellites up there.

Typically, when they’re done with their equipment, scientists kind of just wait until stuff in Earth’s orbit starts deorbiting and eventually burns up in our atmosphere. This natural process, however, can take a very (very) long time.

Thus, hoping to pave a cleaner future for our space-y dreams, the European Space Agency announced the strengthening promise of its innovative, prototype aluminum-coated sail. This device can ride up to orbit with a satellite and help it deorbit whenever.

The concept is called the Drag Augmentation Deorbiting System, or ADEO, braking sail — and in late December, the smallest of its kind completed its final successful demo mission since the program’s seminal one in 2018.

An artist’s impression of ESA’s prototype braking sail concept.

ESA

How does it work?

Basically, ESA folded up the 3.5-square meter (38-foot) sail until it could fit in what essentially looks like a 10 centimeter (4 inch) jack-in-the-box package. Scientists then attached the component to a privately built spacecraft called the ION satellite carrier. ION was launched via a Falcon 9 rocket on June 30, 2021.

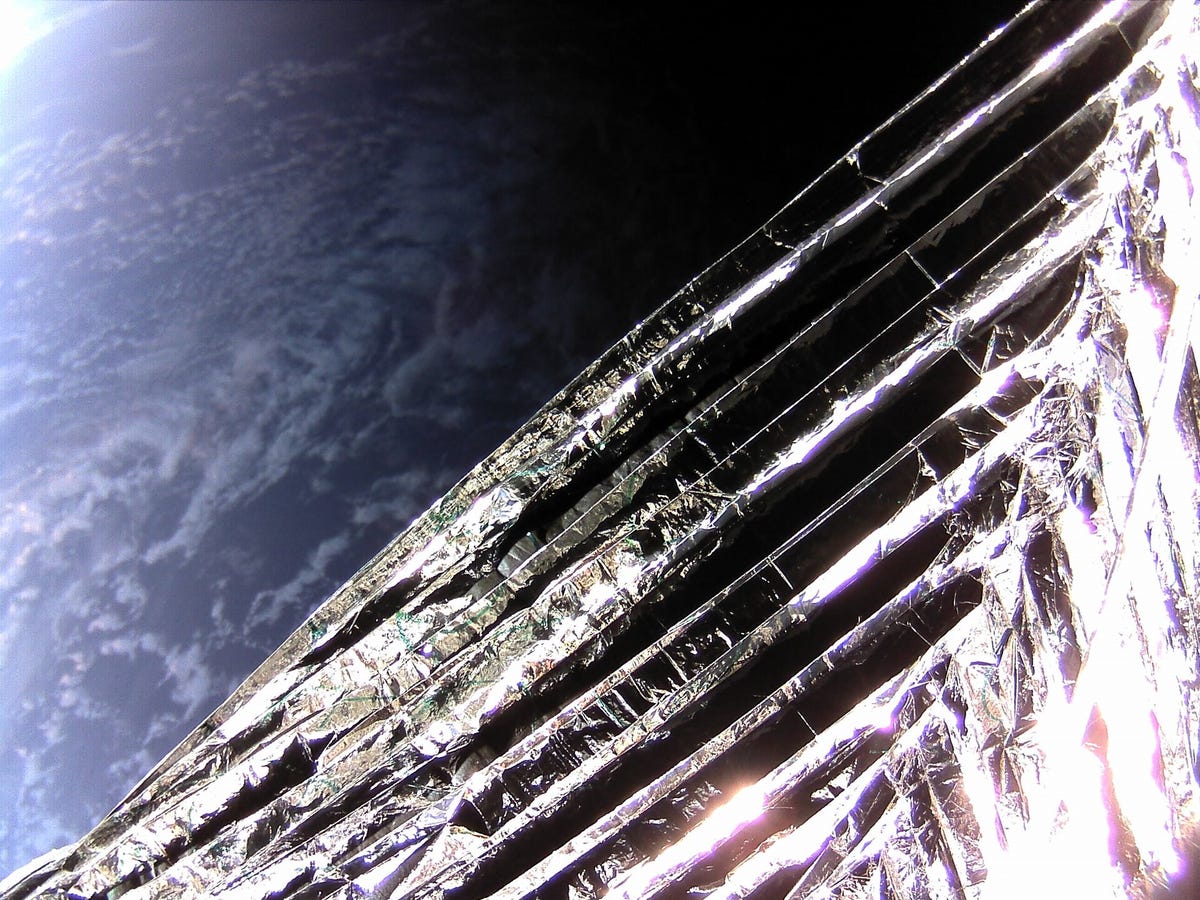

Then, in December 2022, the sail was deployed to showcase a silvery polyamide membrane secured to four carbon reinforced arms positioned in an X-shape. That increased what’s known as the satellite carrier’s atmospheric surface drag, which refers to a force generated by atoms near the top of the atmosphere that travel opposite to the relative motion of something in low Earth orbit. You can think of drag as friction, but with air.

With such a bolstered drag effect, the spacecraft started lowering its orbital altitude at an accelerated pace to expedite the satellite’s ultimate demise: burning up in Earth’s atmosphere.

“The ADEO-N sail will ensure that the satellite will re-enter in around one year and three months, while otherwise it would have reentered in four to five years,” Tiziana Cardone, an ESA structural engineer who oversaw the project, said in a statement.

A camera view from the ION satellite after it unfurled the sail.

HTS

For a wonderful mental picture of all this, ESA thinks of the silver sail as the satellite’s “angel wings,” softly helping it float toward its death. The official name of ADEO’s latest mission was, aptly, “Show Me Your Wings.”

Going forward, the agency says this scale can also be scaled up or down depending on what kind of satellite it’s connected to.

“The largest variation can be as big as 100 square meters and take up to 45 [minutes] to deploy,” the agency said in a press release. “The smallest sail is just 3.5 square meters and deploy in just 0.8 seconds!”

Passive drag systems like this one aren’t exactly a new concept. According to NASA, such devices represent the most “common deorbit device” for satellites orbiting in low Earth orbit, and present an advantage because they’re quite easy to deal with and can be stored super compactly.

But what’s striking about ESA’s recent achievement with ADEO is that it seems to be working extremely well, keeping in line with widespread efforts to mitigate the huge issue of space junk. Last year, for instance, the Federal Communications Commission adopted a new “five-year rule” for deorbiting satellites, down from the previous 25 years, and ESA itself has a major initiative to address space pollution.

“We want to establish a zero debris policy, which means if you bring a spacecraft into orbit you have to remove it,” Josef Aschbacher, ESA’s director general, said in a statement last year.